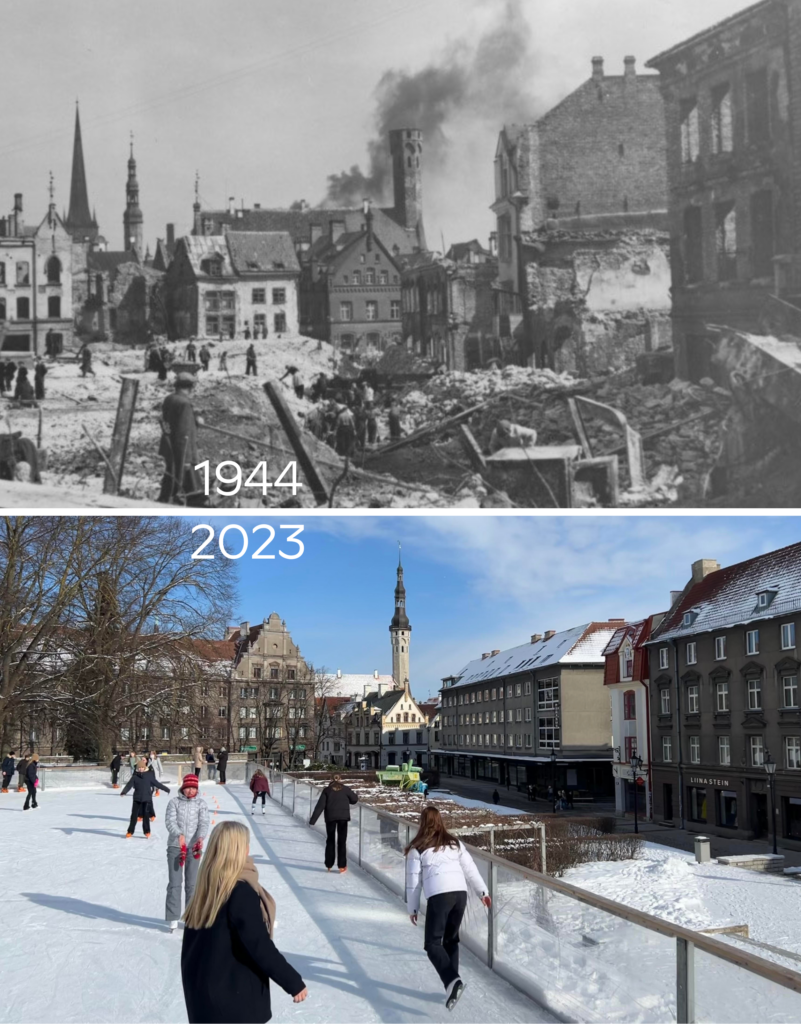

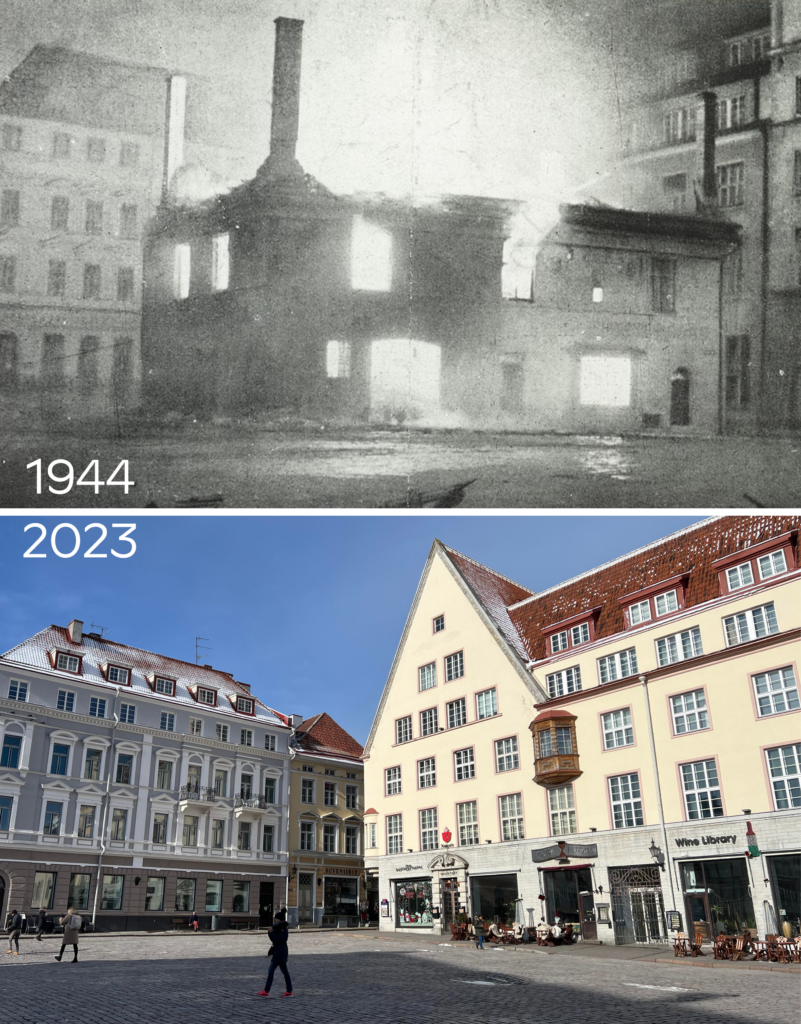

On 9 March 1944, Tallinn was devastated by the March bombings, which destroyed a quarter of the city almost overnight; Adam Rang, whose family members lost their home that night, reflects on how the bombings changed Estonia – and recreated the photos to show how present-day Tallinn has recovered.

The scale of the devastation inflicted on Tallinn in March 1944 is not immediately obvious to the tourists that flock to its postcard-perfect Old Town today.

But the clues are all around. The best place to start is right under your feet. What may at first seem like haphazard pavement patterns, like here below on Harju Street, actually tell a deeper story.

They mark where buildings once stood until the night of 9 March 1944 when around a quarter of Tallinn was destroyed, almost overnight, in waves of Soviet bombings.

Up to 300 Red Army aircraft were involved and their primary targets were residential districts, as well as cultural landmarks, including the national theatre, a church and a synagogue, hospitals, cinemas and hotels. Flares were dropped first to ensure they were clearly visible to bombers. To ensure maximum devastation, Soviet saboteurs on the ground had already snuck in early to blow up the water pumping stations needed by fire brigades.

More than 600 civilians were killed and around the same number were injured; more than 20,000 became instantly homeless – and a mass exodus from the country to escape further attacks would begin.

The Estonia Theatre was a key symbol of Estonian culture and where the first Estonian parliament had convened after the country declared independence in 1918. It was utterly destroyed.

As the bombers approached in the night, the first Estonian ballet, “Kratt” – based on old Estonian mythology – was being performed on stage. The performers had to run out into the street, still in their devilish costumes while the city burned around them. The spectacle, even for those who didn’t see it themselves, would be seared into Estonia’s collective memory.

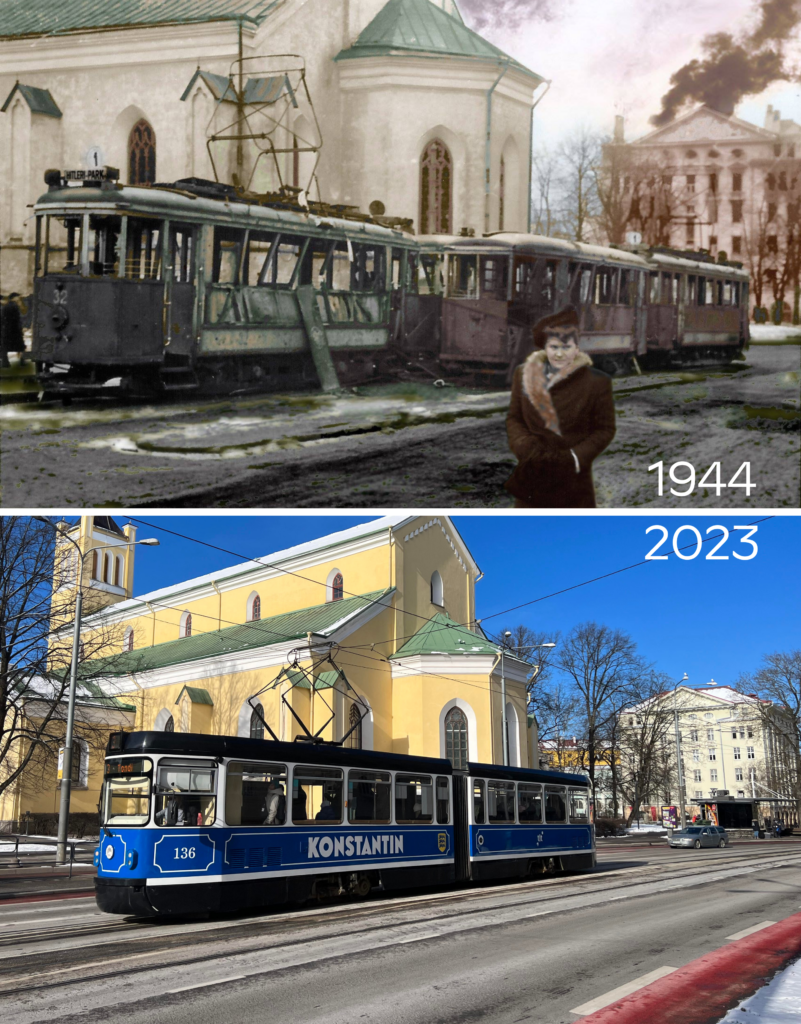

Bombs also hit the iconic St. Nicholas’ Church, obliterating almost everything inside, including its ornate pews, pulpit, balconies and epitaphs.

The Nazi-Soviet road to ruins

The tragedy really began in August 1939 when Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union together signed what they called their “non-aggression pact”. Yet it contained a secret protocol to aggressively tear up international law and divide sovereign European nations between them, beginning the Second World War – in which both totalitarian powers continued to provide mutual assistance for the following years.

The Baltic countries were allocated to the Soviet “sphere of influence” so were invaded by the Red Army, which overthrew Baltic governments, staged illegal annexations and unleashed devastating repression, including mass deportations mostly targeting women and children.

However, the Nazi war machine – which the Soviets had contributed to – eventually turned on the Soviet regime, too, interrupting its occupation of the Baltic countries with a devastating war that resulted in the local population being conscripted to both sides, sometimes having to fight against their own family members.

The Baltic countries were invaded and occupied again, next by the Nazis who unleashed yet further repression, most brutally targeted at the Jewish community.

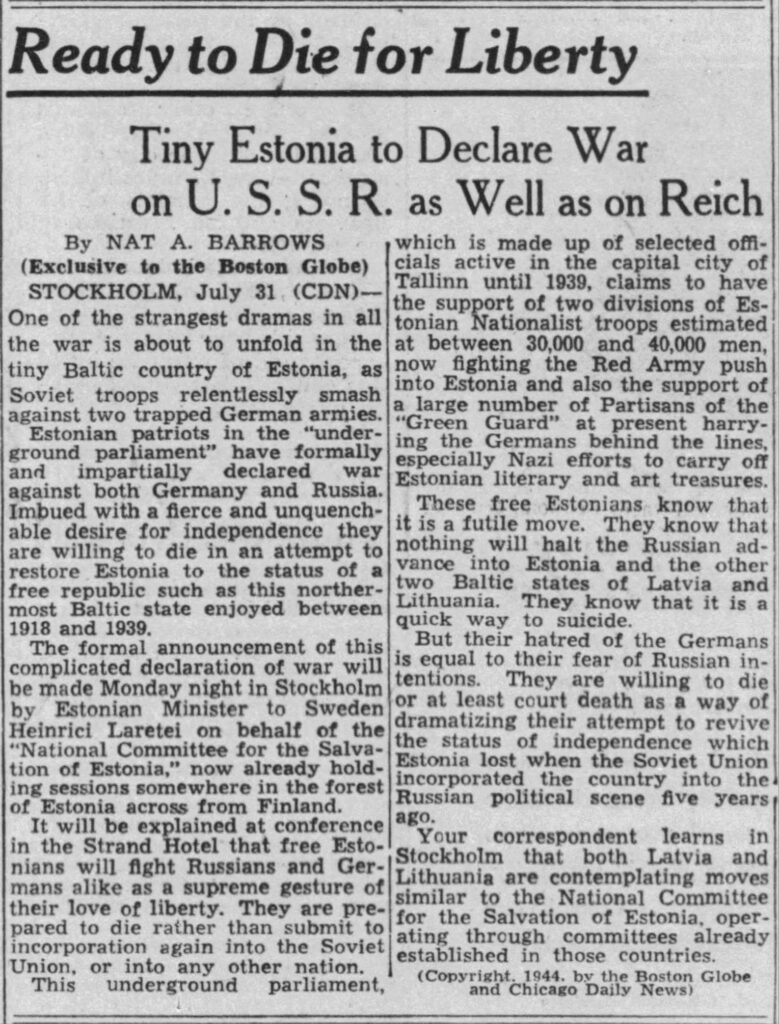

By 1944, the Soviets were preparing to invade the Baltic countries again but launched its bombing campaign throughout March (and again later in the year) across Estonia primarily at local populations, in an attempt to wear down resistance to yet further occupation after the Nazi occupiers had fled.

The Estonian town of Narva was the first to face mass Soviet bombings in February. The entirety of the town was near totally destroyed.

After the Nazi retreat, Estonians raised their own flag once again and re-affirmed their independence in the hope that the world war would eventually end with the restoration of all pre-war territorial integrity.

However, the advancing Soviets tore down flags of Estonia and would continue their brutal occupation of the Baltic countries – as originally agreed with the Nazis – for nearly half a century more, while unleashing deeper repression against local populations, including by scaling up its mass deportations.

Unfaded memories

While the Soviets initially dropped leaflets after their bombs to justify the destruction, they fell immediately silent on the topic after their own occupation resumed.

Any talk of the bombings was heavily censored. Even the dead weren’t left to rest. At Liiva cemetery, the section dedicated to victims who perished in the bombings was wiped away with new graves dedicated to Red Army soldiers.

The coverup didn’t work, though. The knowledge of the bombings was passed down through Estonian families and subtly alluded to in Estonian art and literature, evading censors.

Below, a woman in 1944 stands amid ruins looking up the street at what was left of St. Nicholas’ Church. Behind her are the ruins of houses, which would be left empty for decades until that spot was rebuilt as the Estonian Writer’s Union, which would also serve as a home to writers in Estonia, such as Jaan Kross. At the time of the bombings, Kross was a yonug man persecuted by the Nazi occupiers and had been arrested for supporting Estonian independence. He lost his home that night too. Later, under Soviet rule, he would continue to challenge the occupation, while becoming Estonia’s most internationally acclaimed writer.

Today, a statue of Kross stands on that corner gazing eternally at the home where he lived out the rest of his life, long enough to see Estonia’s independence restored, after which he helped write its new constitution.

Kross focused on themes of state censorship and repression. On the surface, his stories often focused on the historical relationship between Estonians and their feudal overlords, but Estonians knew that it could also be read as a critique of ongoing historical oppression, such as in his most celebrated series of novels, “Between Three Plagues”, which highlighted how Estonia suffered at the hands of warring empires. The plagues in the story were in one sense literal, but also a reference to the plagues of Soviet, Nazi, then Soviet again, occupation.

Mythologies grew up around the March bombings, mostly centred on the Estonia Theatre. When it was rebuilt, trees were planted around it, and the people of Tallinn began to whisper that when the trees would reach full life then Estonia would be liberated from Soviet occupation.

One aspect of the tragedy was unknown to Estonians at the time of the bombings, however. While Estonians opposed both Soviet and Nazi occupations, the fact that both powers had originally colluded together to agree the Soviet occupation was kept hidden for decades. After the Nazis had been defeated, the Soviets still based their illegal Soviet annexation of the Baltic countries on the staged process that was conducted with Nazi agreement.

As momentum eventually built towards restoring independence, the Soviet region introduced a policy of glasnost that allowed greater freedom of speech. It was meant to let some pressure out of the system, but the surfacing of long publicly suppressed anger against Soviet actions – including the March bombings and mass deportations – only emboldened the re-independence movement. By that point, the full details of the Nazi-Soviet pact (known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact or MRP) had become known to Estonians and formed the basis for the re-independence movement as a rejection of totalitarian imperialism.

The brutality that was intended to subdue a nation’s spirit eventually contributed to setting it free once more.

The same tactics are failing again today in Ukraine where bombings targeted at civilians – and even the return of mass deportations – are intended to pave the way for illegal annexation but have actually strengthened Ukraine’s determination to resist as a unified independent nation. As Estonia has shown, that sentiment won’t diminish even generations later.

Tallinn is illuminated with fire again every 9 March as night falls, but the flames these days are from hundreds of candles placed along Harju Street where buildings once stood and families once lived, ensuring they will never be forgotten.

* This article was originally published on 9 March 2023.

A small smile so long down the track – my Mom was at the ‘Kratt’ performance where after the shock event everyone tried to escape and save life whichever way possible . . . once she had fallen from bomb crater to bomb crater trying to cross the very short distance to Kaupmehe street she had to admit one of the big shocks on the street was to see “Kratt’ In his scary costume trying to find his own way out of the scenario’! Hell!