The US policy of not recognising the annexation of the Baltic states formed an international anchor which fostered the hope that justice would one day prevail, and strongly influenced the behaviour of other Western states for 50 years.*

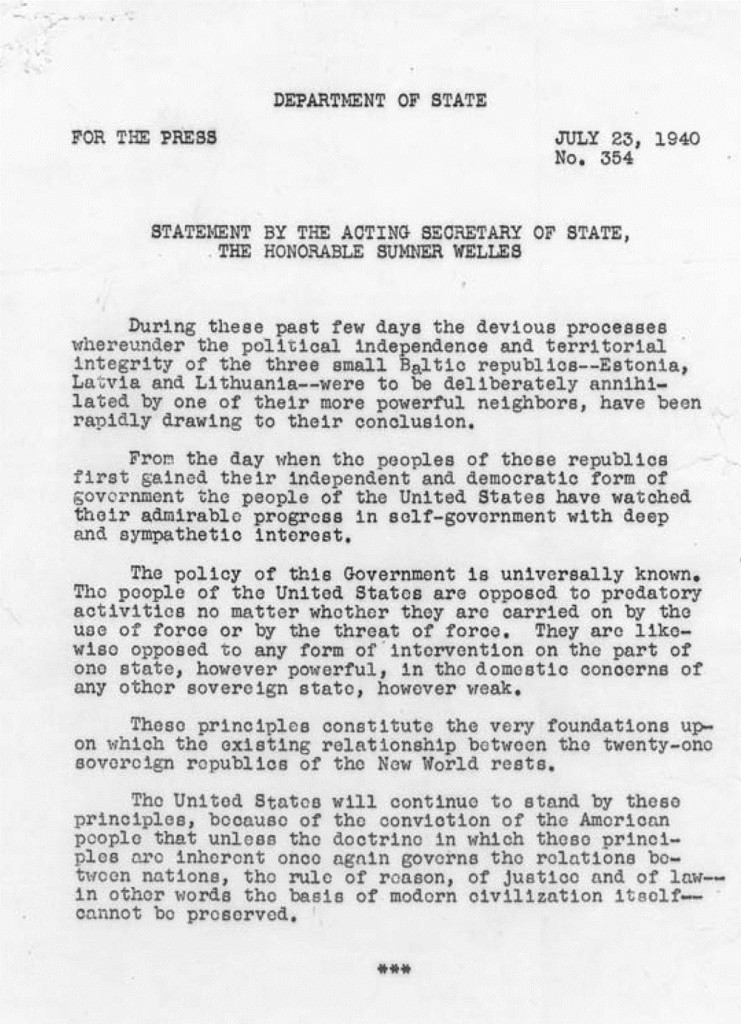

The Welles Declaration

My experience is that the US – the biggest Western democracy – has helped Estonia and the Baltic states the most with their legal and moral position in assessing the Soviet occupation and annexation of 1940. The publication of the declaration by acting Secretary of State Sumner Welles (substituting for Cordell Hull) on 23 July 1940 truly deserves to be celebrated, even 76 years later.

This official position of the US government identified the activity of the Stalin-led Soviet Union as a breach of international law and rules, and confirmed that the US would not recognise the violent change of the status and political regime of small states.

Naturally, it could have been claimed back then that the Sumner Welles declaration provided no specific assistance to Estonia, which was suffering from Soviet communist terror.

However, we can now say that this position adopted by a large democratic state had a clear effect for the subsequent half-century. The US policy of non-recognition shaped an international political and legal axis that supported the pursuits of various movements, both in exile and at home, in trying to liberate the Baltic nations.

Firstly, when the US adopted this position, it encouraged other Western democracies to do the same. Without the Sumner Welles declaration, it would have been unlikely that the UK, France, Canada or Australia would have treated the matter as unambiguously, especially during the Cold War.

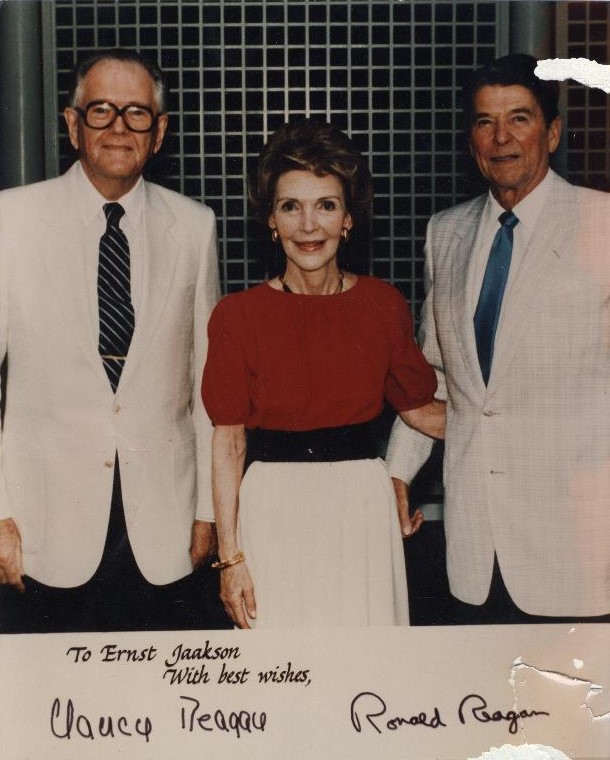

Secondly, the non-recognition policy guaranteed that the diplomatic representations of the occupied Baltic states retained their status as members of the diplomatic corps in the US. The Latvian and Lithuanian embassies in Washington continued their activity until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Although the Republic of Estonia unfortunately had not had the time to establish an embassy in the US capital, the main consulate in New York, led by Ernst Jaakson, fulfilled the role of a diplomatic representation.

In addition, the principle of the Baltic states’ legal continuity provided the opportunity to maintain and, if necessary, expand the activity of honorary consuls, such as Jaak Treiman in Los Angeles.

Annoying thorn in the side of the Soviets

We can only imagine what an uncomfortable and constantly annoying thorn in the side of the Soviet authorities was the status of the Baltic representatives in the Washington diplomatic corps. It was a consistent public reminder that the status of the Baltic states in the Soviet empire was the result of devious and predatory activities (to borrow the style of Sumner Welles). It was also a constant indirect allusion to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which made the annexation of the Baltic states possible for the Soviet Union.

Thirdly, as the Baltic countries continued to be occupied, the value of the US non-recognition policy gradually became evident to the Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians who lived in their homelands. The fact that the world’s most powerful country did not consider Estonia’s membership in the Soviet empire to be lawful became the only ray of hope in the gloomy reality of a totalitarian regime for many patriotically minded Estonians.

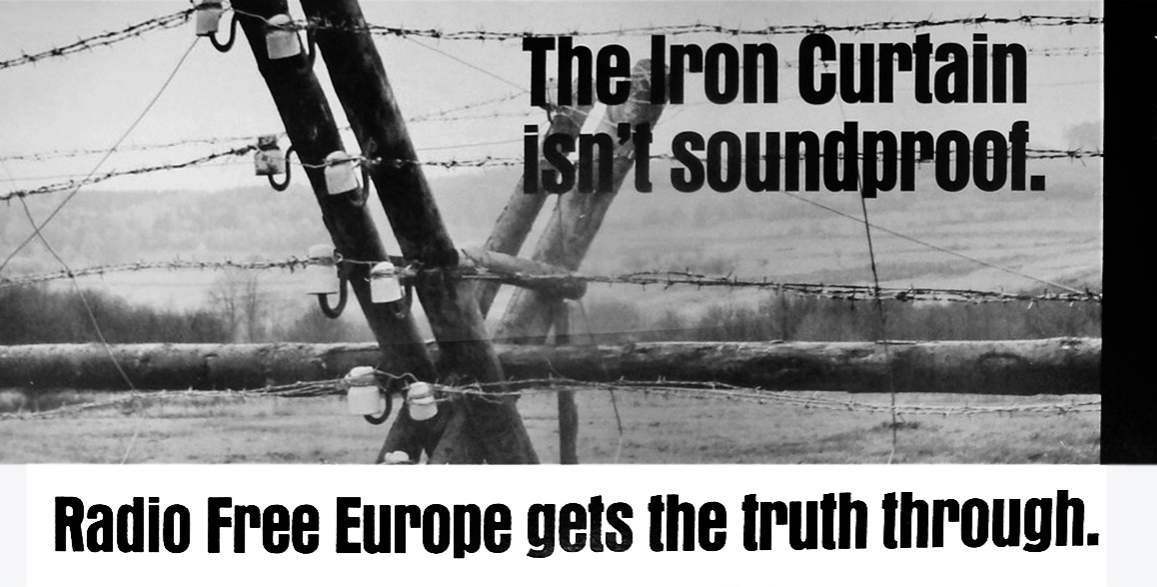

Each year on 24 February (the Estonian Independence Day), thousands of ears were pressed close to their wireless sets to hear, through the crackling generated by radio jammers, broadcasts of festive assemblies organised by Estonian expatriate organisations, the Estonian national anthem and the US president’s annual message to Consul-General Ernst Jaakson, expressing the hope that Estonia would become free again one day.

President Ronald Reagan pronounced a similarly strong message in July 1983 with a statement to the UN General Assembly, presented by Ambassador Jeanne Kirkpatrick:

Americans share the just aspirations of the people of the Baltic nations for national independence. We cannot remain silent in the face of the continued refusal of the government of the USSR to allow these people to be free. We uphold their right to determine their own national destiny, a right contained in the Helsinki Declaration which affirms that “all people always have the right, in full freedom, to determine, when and as they wish, their internal and external political status, without external interference, and to pursue as they wish their political, economic, social and cultural development.

Fourthly, although Stalin may not have cared about the non-recognition of his conquests, the US position had a hidden effect on his successors. The knowledge that the democratic world did not treat the Baltic states as a lawful part of the USSR must inevitably have made the Kremlin somewhat hesitant. We may suppose that the knowledge made them more cautious in attempting to completely sovietise the Baltic nations, hindered the authorities’ plans to that effect and, to some extent, gave a bigger cultural and economic breathing space. After all, they were considered the “Soviet West”.

Realpolitik bites

Today, we must be especially grateful to the leaders and politicians who, for 50 years managed to maintain the legal and moral position that the United States had adopted in 1940. Maintaining it was much harder than publishing the Sumner Welles declaration. The realpolitik of the times meant that Washington’s position was consistently attacked with varying intensity.

The first period of crisis for the policy lasted from the late 1960s to the 1970s. The peak of the Cold War had passed and was replaced with coexistence that meant creating a peace through the balance of power and concentrating on avoiding a nuclear conflict.

In that new situation, America’s tenacious refusal to acknowledge the Baltic states as part of the USSR started to seem not only an anachronism but also a hindrance to achieving agreements with the Kremlin on the most pressing matters. Many refugees despaired and were harangued into coming to terms with real life.

Australia’s Labour Party gets cosy with the Soviets

The door to realpolitik was opened by Gough Whitlam’s Labour government that came to power in Australia and decided to start formally recognising the annexation of the Baltic states in 1973. Surprisingly, this turned out to be a positive development, an incentive that encouraged Baltic refugees to protest all over the world. The result was that the conservative government that followed Whitlam’s dismissal (in 1975) resumed the policy of non-recognition. This was an important victory that blocked the wider spread of realpolitik.

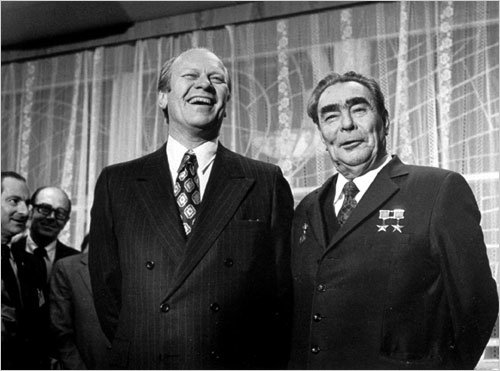

In the US, preparing for the 1975 Helsinki Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) was a critical period for the non-recognition policy, as one of the main issues at the conference was the recognition of existing borders.

In 1975, information was leaked to the US press according to which Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and the National Security Council were considering legalising the annexation of the Baltic states to relieve tensions. A State Department official said the hope of the USSR surrendering the Baltic states was as “realistic” as the belief that the southern states of the US that lost the Civil War would once again form a confederation.

Gerald Ford stands his ground

The newly sworn-in US president, Gerald Ford, who had replaced Richard Nixon six months earlier, was under heavy pressure. The American media thought that the only factor hindering the abandonment of the policy was the US Congress, which was believed to be sensitive about losing the votes of their Baltic-born constituents.

However, Ford – who had no experience of foreign policy – turned out to be more principled than diplomats expected. He met the leaders of Baltic organisations twice prior to the 1975 Helsinki conference, was warm and positive towards them and confirmed that he would maintain a firm position on the matter.

In 1976 Ford agreed to be the patron of ESTO (a festival organised by Estonian expatriates) in Baltimore. In his address, Ford declared that the US would continue to support Eastern European nations’ pursuit of freedom and independence with all appropriate and peaceful means, emphasising that the principles of territorial integrity of the Helsinki Final Act included a clause under which no occupation or acquisition achieved in contravention of international law would be recognised as legal.

The US congress as the most effective ally for the Baltic people

The US congress has always been the most effective ally and channel of influence for Baltic refugees. If one wanted to inform the public about the fate of Estonia, it was easy to turn to one’s local congressman by mail or telephone, or visit them personally.

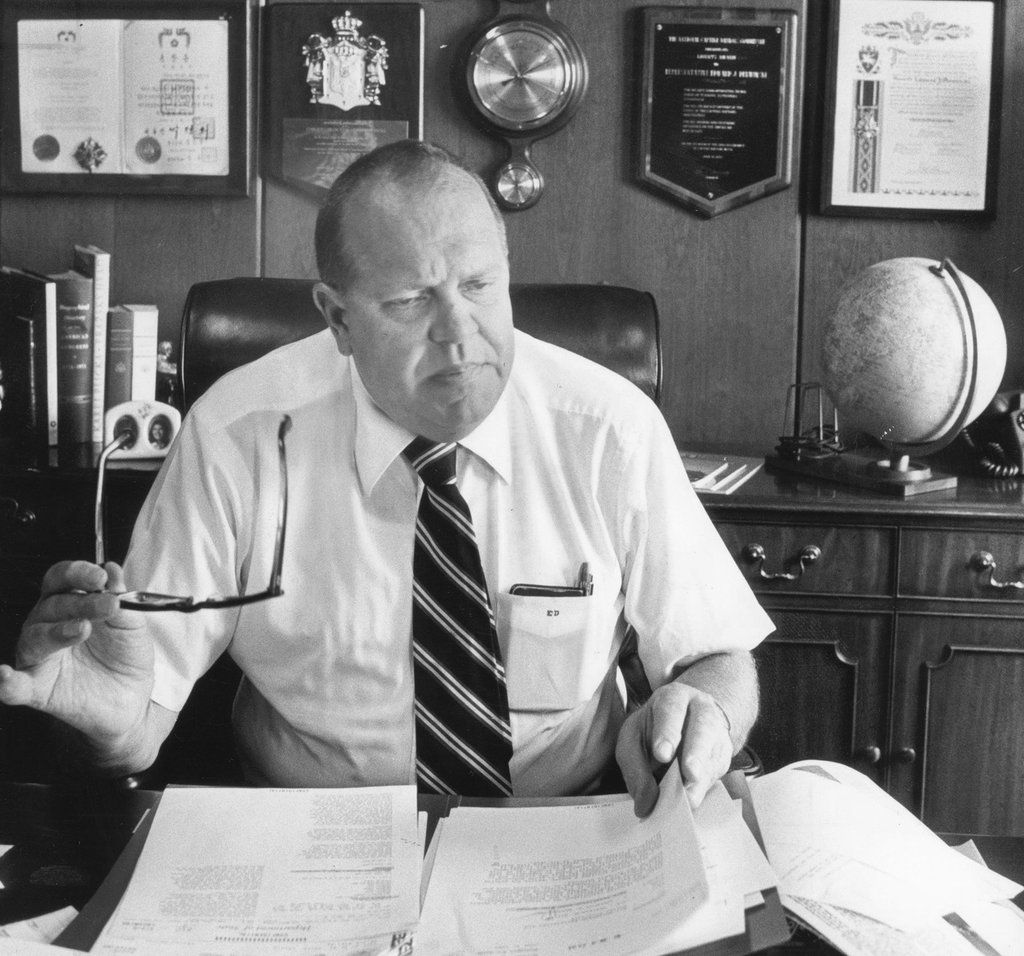

Several members of the congress who had an Eastern European background were especially empathetic towards the Baltic question. In the critical year of 1975, our “guardian angel” was Congressman Edward Derwinski, who had Polish roots. He submitted a draft resolution to the congress in March that year demanding that the US delegation to the Helsinki conference continue with the non-recognition policy.

However, it is true that members of the congress were also influenced by the main trends in realpolitik. Nevertheless, most were prepared to agree with the legal and moral arguments concerning the Baltic nations.

When I was organising an address signed by members of the congress on the occasion of the 50th birthday of Mart Niklus, an Estonian who was at the time imprisoned in the USSR, I met Senator Robert Dole. His first reaction was that there was “not much hope for those poor little countries”.

My argument was that, on the contrary, people in the Baltics had not lost hope; many of them were fighting bravely for their basic rights. Our job was to encourage and support them. Dole warmed to this and not only signed the letter to Niklus but even sent a “Dear Colleague” letter co-signed by Senator Dennis DeConcini recommending that other senators do the same.

In the 1980s the Baltic question was hot in US politics, the more so thanks to President Reagan, who signed the Baltic Freedom Day proclamation in June each year starting from 1982. That initiative actually came from the Congress, which passed a resolution due to the lobbying of Baltic organisations. The leading organisation representing Estonians was the Estonian American National Council (EANC).

An example of the influence of Baltic friends in the congress on events in Estonia was the message by 20 senators to Mikhail Gorbachev (the last Soviet leader) ahead of the 23 August 1987 demonstration in Hirvepark, Tallinn, marking the 50th anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Its authors wrote that granting permission to hold a peaceful commemoration ceremony was connected to the freedom of speech and assembly that the Soviet leader had permitted in the USSR and the exercise of which he had apparently promised to guarantee.

The senators demanded that the organisers of the event in Tallinn would not be persecuted and that the meeting would be allowed to take place without interference. The message was presented to the Soviet ambassador in Washington and to the secretaries of the Communist Party in the Baltic states, including Karl Vaino (the Estonian communist leader at the time).

The position of the US senators was broadcast on Voice of America radio three days before the planned meeting. It could be said that this high-level address neutralised Soviet plans to suppress the event and helped gradually to gain acceptance for future national mass events.

However, it must be added that the senators did not dream up the initiative themselves. Having learnt of the upcoming commemoration of the Soviet-Nazi Pact, Baltic American activists prepared the congress and the media for it.

As the members of the congress already knew us from many Baltic-related campaigns, the problem was not over the essence of the event but rather the technical execution of the message: the congress was on vacation in August. It was only because we were known and trusted that we had the chance to get the senators’ support rapidly in a limited time – two or three days – as their staff contacted them during their holidays. We proposed the original text of the message, which the senators naturally edited.

The media awakens to Baltic issue

Working with the American media was even more important. As we were able to direct their attention to what was to take place in Tallinn on 23 August before it happened (the effect was boosted, in turn, by the senators’ letter to Gorbachev), the next day – 24 August – the message of the Baltic nations broke through to mainstream media for the first time.

The Hirvepark meeting and its demands on disclosing historical truths were front-page news in nearly all the largest US papers. From that time on, the Baltic problem was in the sphere of interest of American journalism.

The next, even greater, breakthrough in terms of coverage in the international media was the Baltic Way (on 23 August 1989, approximately two million people formed a human chain spanning 675.5 kilometres (419.7 mi) across Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania two years later.

Washington avoids “rocking the boat”

As attempts to restore the independence of the Baltic nations became more pointed in the late 1980s and early 1990s, realpolitik paradoxically made another comeback.

The arms limitation talks between the US and the USSR, and the fact that the USSR was starting to pull forces out of Afghanistan in 1988, strengthened the belief that Gorbachev was a reasonable and innovative partner, and this forced the issue of the Baltic states into the background. However, it was in that ambiguous situation that the non-recognition policy proved to be strong and tenacious, and this automatically hindered the attempts of realpolitikers to get the problem off the table.

After President Reagan’s first Moscow visit in May 1988, at a press conference organised by the State Department, I asked Rozanne L. Ridgway, the head of the European department, what the US was planning to do to support the Baltic states’ right to self-determination. The answer was that, as the US did not recognise the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states, they were to be treated as independent countries, which meant that they could already exercise the right of self-determination. Thus, the US did not deem it necessary to deal with the question of that right!

The SS-20 ballistic missiles and Soviet military equipment deployed to the Baltic states in general also became a prominent issue. Did the armaments agreements concluded with the Kremlin apply to the Baltic states, and how was the US planning to check whether the USSR was performing its obligations there?

I explained to Paul Nitze, special advisor on arms control at the State Department, that there were at least as many Soviet forces in occupied Estonia as there were in Afghanistan. Nitze confirmed he was aware of the situation but started to talk about the 400,000 Soviet servicemen who were supposedly still in East Germany.

In the end, the State Department moderator found a compromise: the missile agreement would also apply to the territory of the occupied Baltic states, but that did not mean that the US would recognise the lawfulness of the occupation.

In the following two or three years leading up to August 1991, the Baltics were strongly advised to refrain from “rocking the boat”. The deeper Gorbachev sank into crisis with his internal policy, the more the US administration’s majority wanted to support him, as they believed there was no better partner. Thus, the Baltic nations’ pursuit of freedom seemed especially risky as Washington presumed that the dissolution of the Soviet Union would lead to an international catastrophe.

The irony was that, while the US administration had consistently supported the state continuity of the Baltics for decades, it started seriously to doubt its strategy at the very moment that the restoration of independence was becoming an actual possibility.

A rare exception was Vice President Dan Quayle’s meeting with Tunne Kelam, the chairman of the Congress of Estonia, on 13 September 1990. Quayle said that on the basis of his political intuition the die had already been cast and the Baltic states would continue developing towards achieving full independence. That was the most positive opinion expressed by a senior official of the US during that period. But we must keep in mind that Quayle was not in charge of international relations.

Cautious George H.W. Bush

A good example of the hesitation by US leaders was the meeting between US Baltic organisations and President George H.W. Bush on 11 April 1990.

I compiled a thorough summary of this. President Bush justified the US’s ambiguous policies at the meeting. He said that he had not changed his mind about freedom and self-determination, but emphasised that he had a huge responsibility in promoting freedom and he paradoxically found that duty to be connected to supporting Gorbachev, whose potential unseating he deemed a catastrophe.

The president said it was necessary to act so that “the inevitability of freedom would not be jeopardised”. He complained that he had been unfairly criticised because of his overly soft reaction to the Tiananmen Square massacre in China, and interestingly repeatedly mentioned the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, claiming that the Western states had given false hope to the Hungarians and failed to fulfil their promises, which should not happen again.

We pointed out to the president that the Baltic nations had already started restoring their independence without any external encouragement. We in the US had been preparing for the liberation of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania for all these years. The US had supported our aspirations. This was not the time for last-minute doubts. On the contrary, the US had to show that the non-recognition policy was real, that it had a practical impact on the liberation of the Baltic nations.

The First Gulf War began in August 1990. The fact that the US focused its attention on repelling Iraqi aggression in Kuwait made the Baltic nations feel endangered. It was clear that the new situation offered the Soviet leaders the opportunity to end Baltic “separatism”.

Yelena Bonner, a human rights activist and wife of Andrei Sakharov, warned, in an interview with the New York Times on 28 December 1990 that US willingness to turn a blind eye to Gorbachev’s threats about using force against the Baltic nations would actually encourage the Soviet leader to establish a dictatorship.

We published several interviews and articles soon afterwards (The Washington Post, 4 January 1991; The New York Times, 8 January 1991), one of which was titled “Selling Out the Baltics”. We appealed to the US administration to apply the same principles to the Baltic nations as it had in liberating Kuwait from occupation. In order to stop the Soviet terror apparatus from being used again, Washington needed unequivocally to reaffirm the Baltic nations’ right to independence, instead of concentrating on maintaining the last colonial empire.

Our friends in the congress agreed with these arguments. On 10 January 1991, at the initiative of Donald Riegle, ten senators sent a letter to President Bush, emphasising that it should be explained to Gorbachev in no uncertain terms that US involvement in the Gulf War did not reduce the country’s commitment to the liberty of the Baltic states.

Tensions rise

However, the things we feared did happen. A day after the bloodshed in Vilnius during the Soviet crackdown, the president’s security adviser, Condoleezza Rice, invited representatives of Baltic nations to the White House. The meeting was depressing. Rice concluded that if such things were to occur again “something” would have to be done. But what exactly? I asked, how many Baltic people would have to die before the US would do something. 50? 500? 5,000? She did not answer.

On 22 January 1991, the national security adviser, Brent Scowcroft, invited the heads of three Baltic organisations for a meeting. I was there standing in for Juhan Simonson, President of EANC. President Bush entered the room unexpectedly. It was clear that this was an attempt to calm the Baltic representatives with an unofficial high-level meeting. I tried to convince the president that the US reaction to Gorbachev’s use of force was feeble and, as a result, the Soviet leader might think that the US was weak and would be prepared for appeasement to maintain good relations.

It is interesting that the term “appeasement” had an explosive effect on Bush. He flinched, turned red and practically shouted: “Don’t use that word! Never use THAT word!”

The meeting ended politely but it did not change anything of importance. It had revealed President Bush’s internal moral tensions, which may have emerged from the effort of trying to find a balance between various forces and conflicts. A leader of a democratic state usually has a conscience and the worst – sacrificing the Baltic States on the altar of maintaining US-USSR relations – was perhaps avoided because several parties squashed it.

A lesson for future US presidents

In “At the Highest Levels; the Inside Story of the End of the Cold War” (with Michael Beschloss, Little, Brown, 1993), Strobe Talbott (the former Deputy Secretary of State) recollects what it was like in the Oval Office after the Baltic representatives’ visit.

White House chief of staff John Sununu warned Bush: “This thing is developing into a big political problem for us.” Sununu mentioned that the congress was annoyed and recommended that carefully worded protests against the use of force in the Baltics were not enough; the government needed to “show their teeth” in addition to complaining. A specific result of all the protests was that President Bush decided to postpone a meeting with Gorbachev that was to take place on 11 February 1991, which was a real disappointment for Moscow.

A more distant result of Bush’s hesitant Eastern policy was that he lost the 1992 presidential election because millions of voters with Eastern European backgrounds no longer supported him. The same message should be understood by Donald Trump: if he continues to label NATO as obsolete and is willing to recognise only conditional solidarity, he must be prepared to lose a large number of voters who may be the decisive factor in the event of a close contest.

Happy ending

In conclusion, it can be said that the US policy of not recognising the annexation of the Baltic states formed an international anchor which fostered the hope that justice would one day prevail, and strongly influenced the behaviour of other Western states for 50 years.

The support of a large state is indispensable for small ones, even in today’s international environment. The US is the anchor of NATO without which the organisation would lack power and reliability. However, large states have big problems when they need to adapt quickly to a new situation in which other large partners are involved. The US legal and moral position on the topic of the Baltic states lasted more than 50 years in spite of various short-term pressures – this is unique and is to be commended.

However, in a situation where changes occurred in the blink of an eye, the democratic world needed small pilots like Iceland and Denmark with the courage to act at decisive moments so that the continuity of the Baltic states would become a reality again instead of a theory.

Foreign ministers Jón Baldvin Hannibalsson (Iceland) and Uffe Ellemann-Jensen (Denmark) helped make the transition from not recognising the occupation of Baltic states to immediate restoration of diplomatic relations with the newly independent countries. Nobody protested against this concrete step, and other democratic states followed Iceland and Denmark’s example one by one.

All this emerged from the foundation of the US-initiated non-recognition of the Baltic states’ annexation and support for their legal continuity.

The article was first published in Diplomaatia magazine; published by Estonian World in a lightly edited and amended form on 3 September 2016 and lightly edited on 4 July 2020, 4 July 2021 and 4 July 2022.

Excellent article….Thank you for reminding us of history!

Ms. Kellam’s article is excellent, but of course its focus is what was done by Estonians and Balts in the U.S. As a former member of the Estonian Central Council in Canada I know that similar work was done by Estonian and Baltic groups around the world in those years, exerting huge pressure on the Kremlin. The events of 1990-91 when FREEDOM once again took root show the intense craving for that freedom in the hearts of all Baltic citizens and their families and friends throughout the world. The positive results can be seen in how they have performed on the international stage over the last 30 years.

A beautiful article. I learned much that I had not previously known. Thank you.