The Hotel Viru is an iconic hotel in the centre of Tallinn, the Estonian capital, where, during the Soviet occupation, many foreign, mostly Finnish, tourists were accommodated – and it was also a hotbed for the KGB.

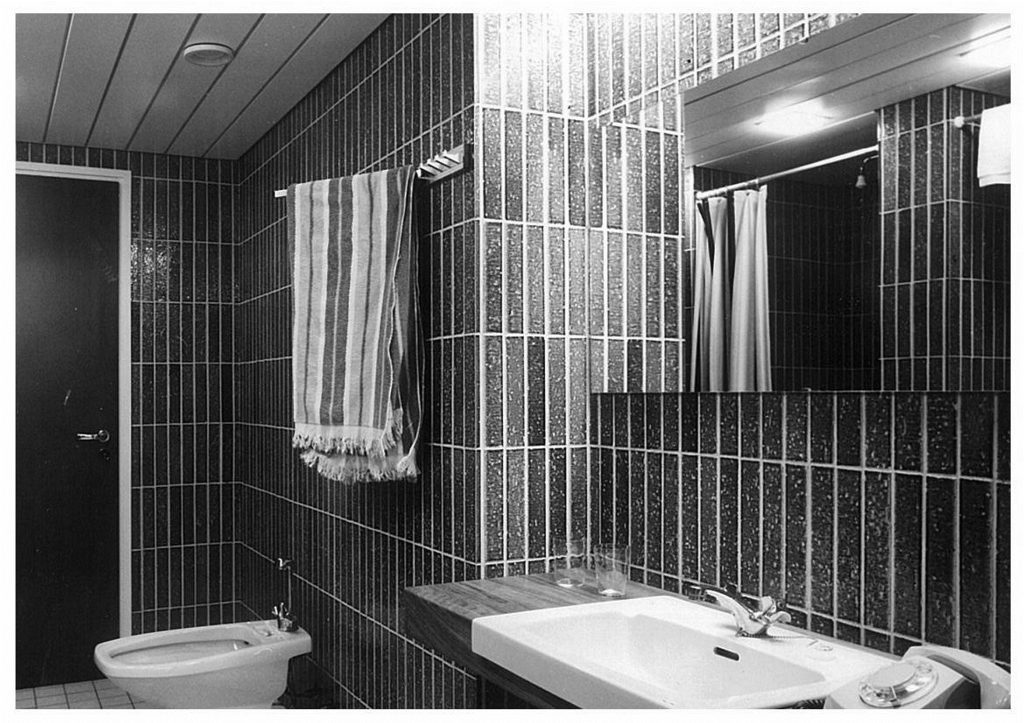

The Hotel Viru was built in 1972. From the outside, it looks much like it did when it was built, but inside, the hidden 23rd floor reveals an eerie past of KGB surveillance. The hotel is, these days, a symbol of the KGB espionage with it’s bugged ashtrays and “special rooms” for “special guests”.

Officially, as the elevator displays, the Hotel Viru has 22 floors. The 23rd floor housed the KGB radio centre, where agents were stationed to intercept radio signals and relay information back to the Soviet government. The radio centre was built in 1975, which corresponded to the pan-European joint security conference that was taking place in the Finnish capital, Helsinki, and would be attended by the then-Secretary General of the Soviet Union, Leonid Brezhnev. The signal from Helsinki reached the 23rd floor of the Hotel Viru and had a direct line to Moscow.

The facilities were used to listen in on the hotel’s most prominent guests, foreign journalists and Estonian exiles. The door to the radio room on the 23rd floor reads, “Zdes’ Nichevo Nyet” or, in English, “There is nothing here” and inside, the room sits untouched since the last KGB agent abruptly left in 1991.

Today, the room is a time capsule of a bygone era of advanced (for the time) surveillance. The musty smell of the abandoned room, now a museum, still lingers. Sheets of paper strewn across the room, smashed radio equipment, and an ashtray filled to the brim with cigarette butts speak to how suddenly the room had been vacated on an August night in 1991 with the collapse of the Soviet Union imminent.

At the height of the Cold War, the room “with nothing there” belonged to the Soviet secret police. KGB agents took shifts listening in on hotel guests through wiretaps placed in ash trays, bread plates and special rooms designated especially for foreign visitors.

After Estonia was occupied by the Soviet Union in 1944, it had almost no contact with the outside world. Until the 1960s, few tourists visited Tallinn. But eventually, “the Soviet Union wanted their piece of the pie”, says a tour guide. In 1963, a ferry line between Helsinki and Tallinn finally opened a window to the other side, bringing in 15,000 tourists a year.

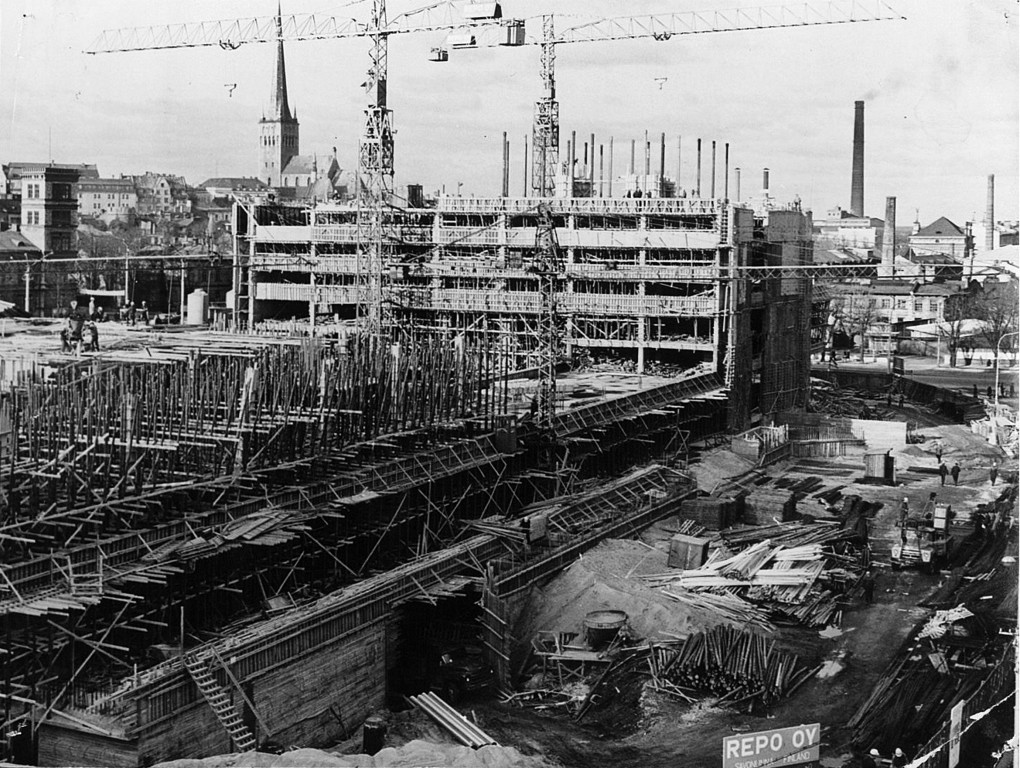

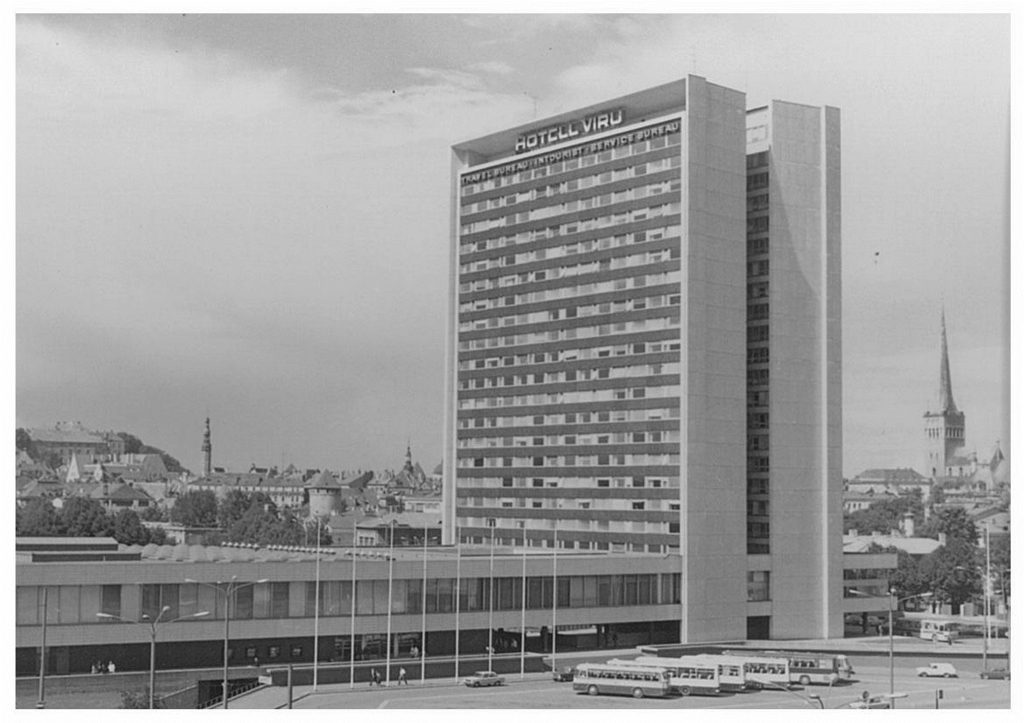

Tallinn’s first “skyscraper”

To meet the growing number foreign visitors, the Hotel Viru was built. It was Tallinn’s first “skyscraper”, a type of building that had never been seen before in Estonia. The Finnish construction company, Repo Oy, was contracted to build the hotel, because unofficially, no one in Estonia knew how to build a high-rise.

The hotel opened in 1972 and was owned by the Soviet Union Foreign Tourism Office and the Foreign Tourism Office of the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic.

While the hotel brought in much-needed hard currency, its foreign guests brought in ideas that threatened the Soviet ideology. The solution: many parts of the hotel would be bugged in order to listen in on many of its guests, especially the Estonian exiles living in the West and foreign journalists.

Sixty guest rooms were bugged and it was no secret to visiting guests. “It was not unlikely that you would get the same room each time you visited,” remarks one returning visitor to the hotel in the 1970s.

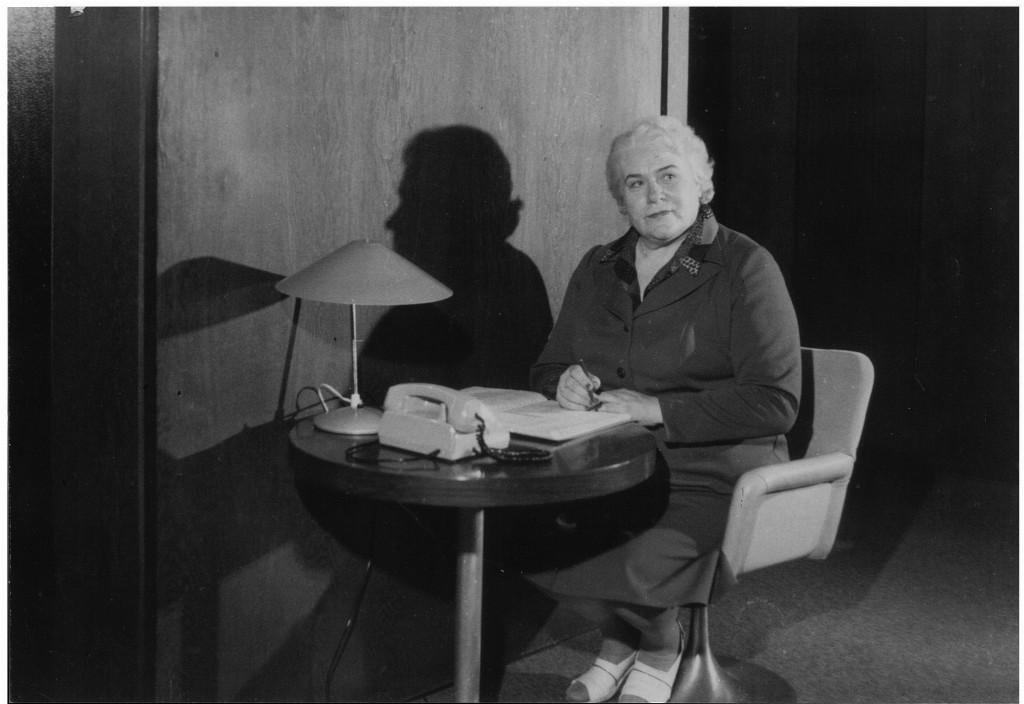

Listening devices and peep holes were hidden in the walls, phones and flowerpots. “Older ladies sat in the corridors recording when you left your hotel room and the time you returned. We walked down the hall towards our room speaking about our day of sightseeing and the lady at the end of the hall held a finger to her lips, warning us we were being listened to,” remarks Ilme, an Estonian exile who visited for the first time in 1976.

The bugged rooms also had their benefits. “You could say out loud in your room you needed soap and it was delivered to your door almost immediately,” says Ingrid, another Estonian exile.

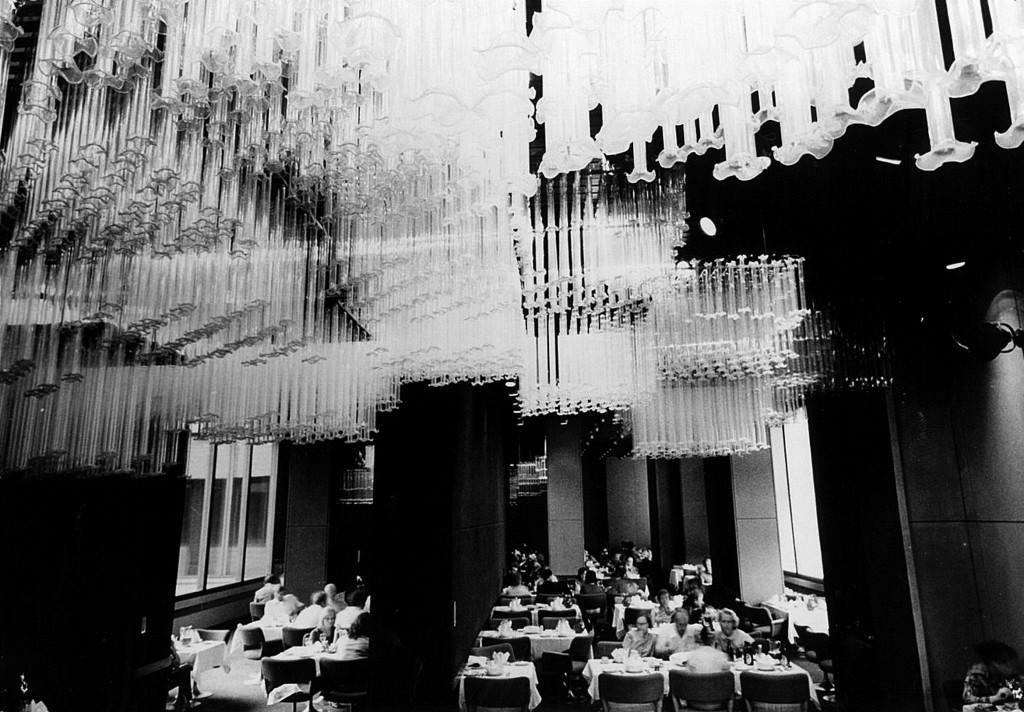

There are hundreds of similar stories from foreign visitors at the time. At the hotel’s restaurant, located conveniently on the 22nd floor – officially, to offer panoramic views of Tallinn to its diners – ashtrays and bread plates held even more listening devices.

“Even if you didn’t smoke, you couldn’t move your ashtray to another table. A waiter would quickly come by and place it on the table again,” says Ingrid, an Estonian exile visiting in the 1970s. “The food was plentiful and even decadent. We ate so much black caviar, something we were not used to, coming from Canada.”

The walls of the sauna were bugged to listen in on Finns discussing business negotiations to be later revealed to their business partners. Foreign journalists were targeted, as the KGB wanted to know exactly what they might say about the Soviet Union when they returned home.

The hotel also had many celebrities visit, including Elizabeth Taylor, astronaut Neil Armstrong, cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova, singers Alla Pugacheva, Jennifer Rush, Nana Mouskouri and Lennox Lewis, the professional boxing heavyweight champion.

The epicentre of city’s nightlife

The hotel was well-equipped with everything measuring up to the Western standards. The restaurant had plenty of food on the menu, something unheard of in Estonia that encountered constant food deficits.

The Hotel Viru offered a racy cabaret and the Valuuta Baar (Currency Bar), where guests could pay in foreign currency and unofficially request female escorts for an evening. “Everything you might want was available, so that guests never needed to leave the hotel,” says Jana Kilter, one of the curators of the KGB museum, now offering tours of the elusive 23rd floor.

If a guest wanted to leave the hotel, special permission needed to be granted. Tourist taxis were readily available to take the hotel guests where they wanted to go, while the taxi driver recorded every conversation and every destination. And if you left the hotel “too often”, a hotel clerk might have asked: “Why are you leaving the hotel so much?”

However, sometimes getting back into the hotel was as difficult as getting out. “One nuance of the Soviet hotels was that foreigners had to have a hotel card – a little piece of paper that served as a kind of pass to get past the beefy security goons that guarded the doors. These guys were presumably keeping average Soviet folks from entering and mingling with the guests,” an Estonian exile remembers. “Presumably some of these people who wanted to get in could have been criminals, but there were also a fair number of black marketeers and people who wanted to buy hard currency on the sly.”

“Anyway, we had one hotel pass for our group of 18, so at one point we were stuck outside the hotel. The guard wouldn’t let us in. We just had to wait until the end of his shift, or when he went to take a smoke break, and then we used the usual trick to get into these hotels (a trick all foreigners knew), which was just to talk really loudly in English and pretend not to understand Russian when they asked for our ‘propusk’.”

Parallel lives

Behind the scenes, the Hotel Viru was outrageously inefficient. 1,080 employees served 829 guests. The older ladies in the corridor, recording the comings and goings on the guests were chosen in particular for their perceived undesirability to foreign men, so they would not marry to escape. Maids were picked for their lack of language skills.

The kitchen ran just as inefficiently. One cook would put food on the plate and two would weigh the portions to make sure nothing had been skimmed off the top. “It all seems so unbelievable now,” says Kilter, “but it was just over 20 years ago.”

In 1990, the situation was more or less the same, according to another visitor. “Getting a hotel room was easy, but there were always two sets of prices – one for foreigners and one for Soviet citizens. At the Hotel Viru, we were offered a room for US$115, an astronomical price in those days, but I had a local friend along and we were able to get the room in her name. The price was 15 rubles, which was exactly $1 at that summer’s black market exchange rate.”

The Hotel Viru’s history reveals the parallel lives that were lived during the Soviet period. There is nostalgia for the good times, for the absurdity of it all, but it is also important not to forget those that suffered under the KGB.

We went on the ‘KBG Tour’ there in 2013 and it was fascinating and fun. The guide (Jana) was great.

Good to read. Thank you.

Interesting…I think maybe different times are being mixed together here. In 1987, you certainly didn’t need permission to leave the hotel and nobody would have used a taxi any more than at home, while Tallinn seemed to be carpeted with drunken Finns and English-speaking Estonians made little attempt to hide their disdain for Russian, Russians and the Soviet Union…