Estonian and expatriate artists share their views on the importance of art in times of crisis along with works that speak to trauma, suffering, hope and empathy.

Although the war in Ukraine weighs heavily on us all, our capacity for unity, compassion and love is palpable. There is perhaps no better testament to this fact than the countless people who are coming together and working towards creation rather than destruction.

In fact, the Estonian Academy of Art has created a scholarship fund for Ukrainian students to continue their studies at the university.

Meanwhile, creators like Mari Kalkun, an Estonian singer-songwriter, wrote a song entitled “Somewhere There’s War”, and Anna Kõuhkna held an auction for one of her paintings as part of the “Art Against War” initiative

They inspired me to ask some of my favourite artists in – or connected with – Estonia: “What role does art serve in times of war and suffering?” Likewise, each artist contributed a work that speaks to their feelings about the war.

Mari Kalkun – Estonian folk musician, singer and composer

I feel that at the moment, we are collectively mourning and grieving for those who are suffering; we feel for them, we care and we cry as one. Music and art help us through this difficult process – it offers contemplation and allows us to let these emotions flow outward.

Art is a conduit for emotions, reflection and putting into words our experiences during times of war and unprecedented terror.

As in traditional culture, when somebody dies lamenting women sing for the deceased and help the community cry out. Hopefully, despite all the horror, we’ll come out of this collective experience as a better, more united society in the end.

Of course, music and art also offer significant hope, lifting the spirit of humanity and manifesting charitable performances and auctions. As an artist, I want to contribute using the power of the medium I know best – song.

Simply put, we have to keep on singing! We have to keep our minds free from fear and take what this mad world is offering us while overcoming the ways it is testing us. I believe words, music and love are stronger than any tank. What’s more, art transcends words, and we are currently dealing with processes beyond words.

Somebody recently said of my new song, “Somewhere There’s War”, “Thank you for singing out what’s a burden on our hearts.”

Olivia Nõgisto – Estonian artist, working in graphic media

For me, art always reflects what is happening in society. On the one hand, it reveals something about society, while on the other hand, it captures the times in which it arises. Artists strive to express and make understandable that which cannot be put into words.

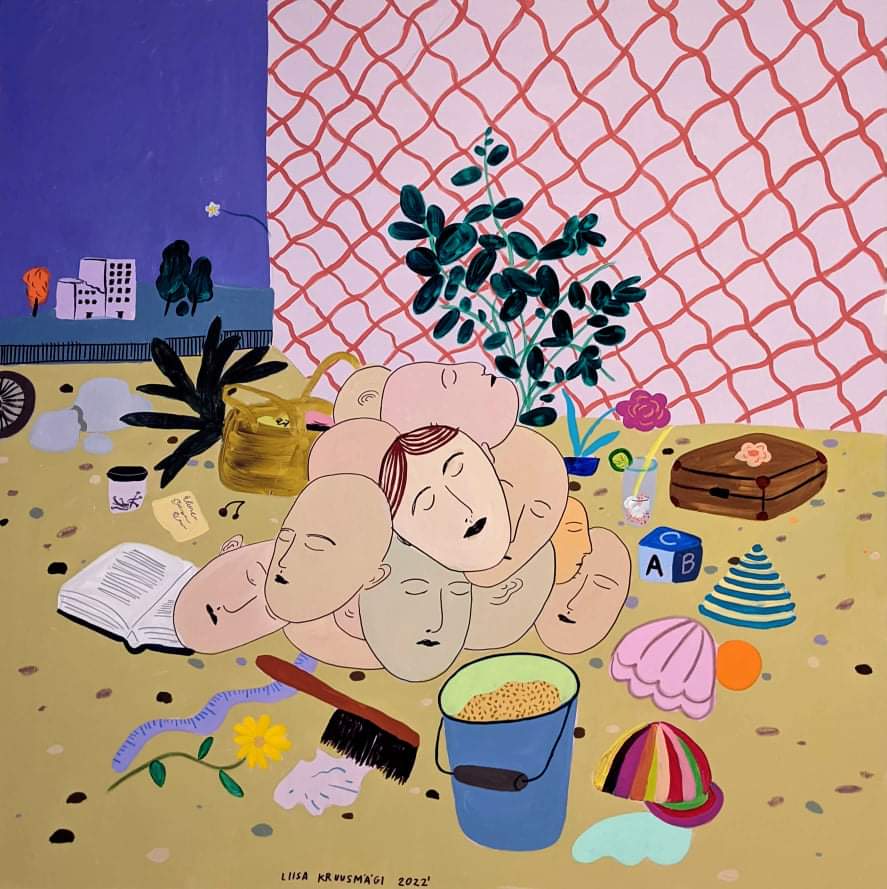

Liisa Kruusmägi – Estonian painter and illustrator

I can share my perspective as an artist and creator. For me, the process of making art is an escape from reality. I can create my own world and I kind of dive into it. It is a very dreamy state, and this feeling can come from colours or composition, as well as a theme or symbols.

But of course, other types of art have the same power. For example, listening to a certain song can lead you to some beautiful memory or another dreamy state. So art can be like a passage into yourself for attaining calmness. I don’t think it’s important to always be present and to know everything that’s happening around you.

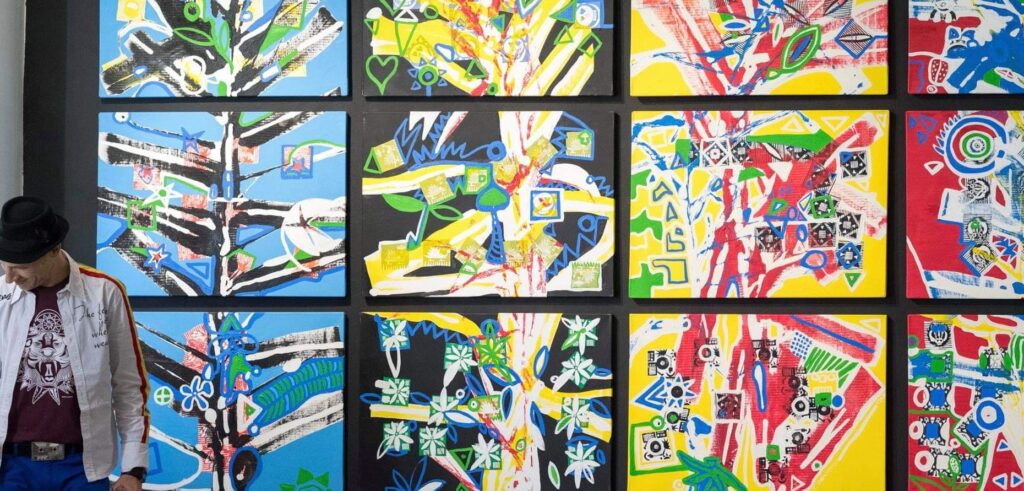

Tarrvi Laamann – Estonian artist and reggae DJ

I apologise if my answer sounds too much like an artist who communicates thoughts and vibrations to the audience. In other words, I don’t discuss art as nature, but rather something I live.

To the question, “What is the use of art in times of war and suffering?” I would say, “An art critic who knows how to look at and appreciate art from a distance probably knows better”. But living in art and creating it with a war raging in Europe, I wonder if art – and the creation of it – is always consolation in these difficult times? The art of peacetime is again a good inspiration for every area of life, and for the benefit of the planet in general so that it does not fly to pieces because of the stupidity of people.

Blessup!

Anna Kõuhkna – Estonian painter, illustrator and photographer

For my answer, I’m going to go with a spiritual-realm kind of response. When all this started happening, I lost my appetite for making art. I was devastated and read the news 24/7, putting all my emotions into it, almost hoping that my sadness, anger, compassion and attention could help in some way. I met fellow artists when we participated in a protest demonstration at Tallinn Freedom Square, and they said the same – they can’t work.

But I began to realise that this state of mind cannot help. Who would benefit from my negative emotions or my unbalanced state of mind when there is enough of that already? I think that only light and love have the power to dissolve what is harmful.

So I changed my mindset, turned off the news and picked up a brush again. It can be art, or it can be the energy of the people – in art, of course, there is energy – that can have a healing impact on anything or anyone.

It may sound insignificant, but I don’t believe it is when it reaches a collective state. If that’s all I can do, then that is what I am doing. In my work, I have always tried to radiate brightness, light and growth. I can only hope it touches or reaches its goal of bringing more of that to the world. If not, then at least I am healing myself when making it, and that is one more person who is healing in this world, like the world needs.

Piret Lindau – Estonian visual artist

In general, I think that art feeds the soul and helps to heal wounds, however, maybe not physical ones. It helps us to move past hard times and facilitates hope. And most often, it simply helps to take our minds somewhere else. And sometimes that’s all we need.

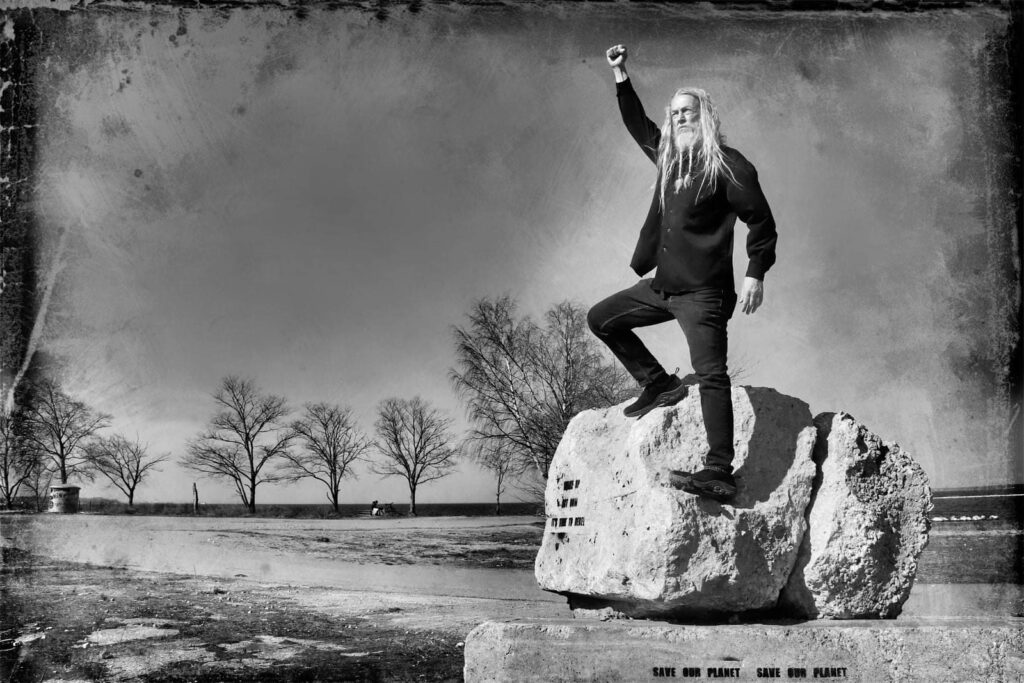

Ron Whitehead – American poet, author and activist, U.S. National Beat Poet Laureate

I have been blessed to spend a great deal of time in Estonia – performing, touring and as a writer-in-residence as part of the UNESCO Tartu City of Literature programme. I love Estonia. In 2019, my sweetheart, Jinn Bug, and I immersed ourselves in the history, culture and literature of Estonia, out of which was born the bilingual edition volume of poems “Nights at the Museum”, translated by Doris Kareva.

I am deeply concerned, worriedly watching the invasion of Ukraine by the tyrant Vladimir Putin. The only weapons I have are my words and my prayers, which I share, with tears, daily.

In 1994, I was blessed and honoured to write “Never Give Up” with His Holiness The Dalai Lama:

Never Give Up

Never give up

No matter what is going on

Never give up

Develop the heart

Too much energy in the world

is spent developing the mind instead of the heart

Develop the heart

Be compassionate

Not just for your friends

but for everyone

Be compassionate

Work for peace

In your heart and in the world

work for peace

And I say again

Never give up

No matter what is going on around you

Never give up

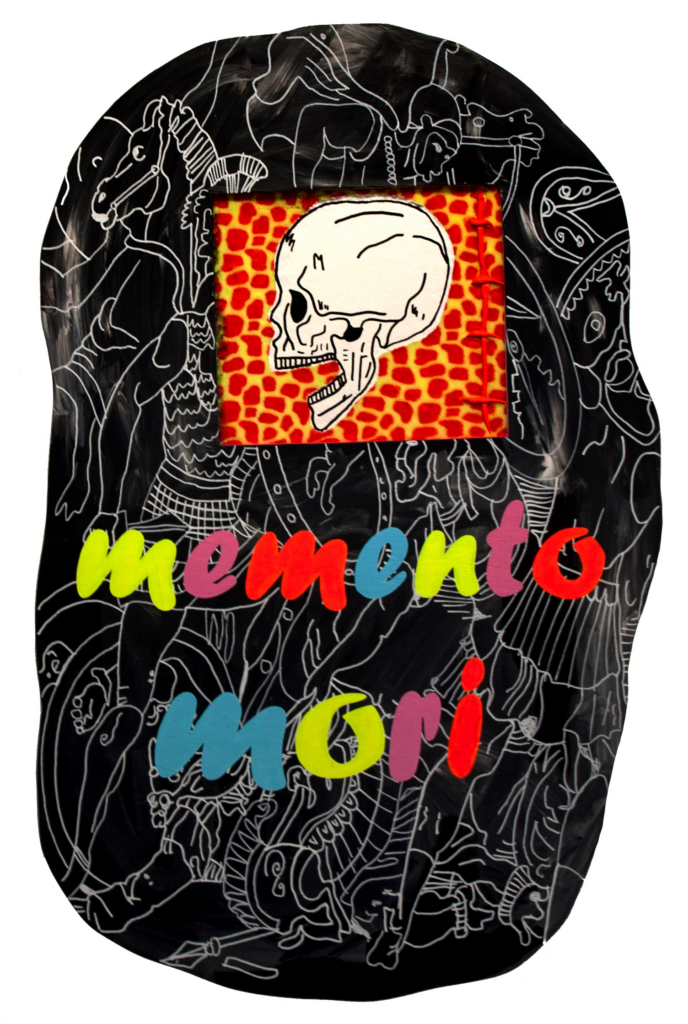

Alina Orav – Estonian painter and installation artist

Living in the 21st century, an era of bio- and nuclear weapons, where one decision can be fatal for a whole nation’s destiny – we should be especially careful making decisions that form international relationships. Especially so since Estonia lies on the border between the Western and Eastern worlds. The outcome is not a movie, nor a video game. War is real. Death is real. The “game” cannot be restarted.

There are many ways artworks and artists can set an example for society. I will focus on one thought that is the closest to me and is the essence of what my work is about.

I think that the ability to see a political situation from various viewpoints can significantly enhance our chances of avoiding war and coming to a mutual understanding as co-habitants of Earth. The aim should be to feel and act together, as “we”, and not to polarise as “them” – or bad people versus us, the good people.

The majority of the most traumatic war crimes throughout history have been made with this mentality. Now, it is imperative that we avoid escalation at all costs, before it is too late.

Art should set an example of how to collaborate and strive towards understanding each other. I suggest this as the main goal because it is the way to avoid war. During times of war, art should encourage our ability to see things from multiple perspectives, to see all colours of the rainbow and shades of grey, to try and see the other side, such that we can come to a mutual understanding and reach common conclusions.

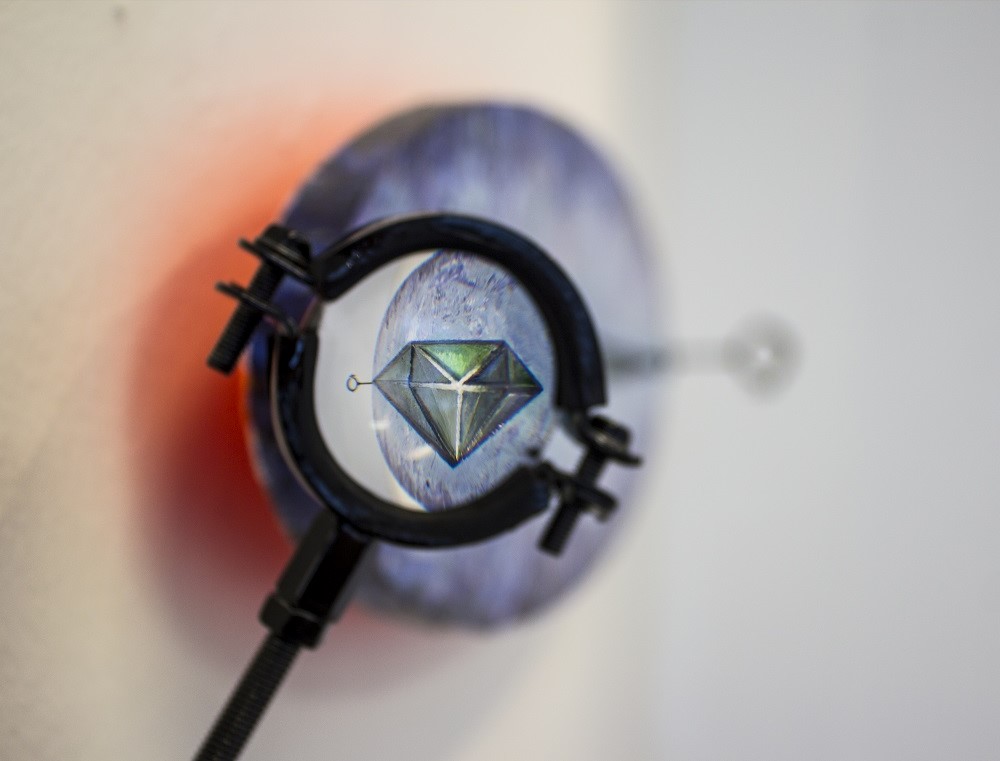

To illustrate this, my artwork here shows one and the same painting from two different angles. Its essence changes as the viewer shifts to another vantage point. This illustrates how one occasion can be interpreted in various ways by different parties and how its essence changes as we approach it from another perspective. This speaks to the essence of any conflict – seeing a situation differently and refusing to acknowledge the other viewpoint. The truth probably lies somewhere in between.

If we were able to picture ourselves in someone else’s shoes, however, it could benefit our ability to collaborate and cooperate, two things that are vital to avoiding war and, as a result, saves lives. This is what really matters in the end.

The artwork shown here was made in 2020 and is surprisingly prophetic – with its two opposing yet simultaneous titles: “Cristalline Solid” from one viewpoint, and “Invasion” from the other.

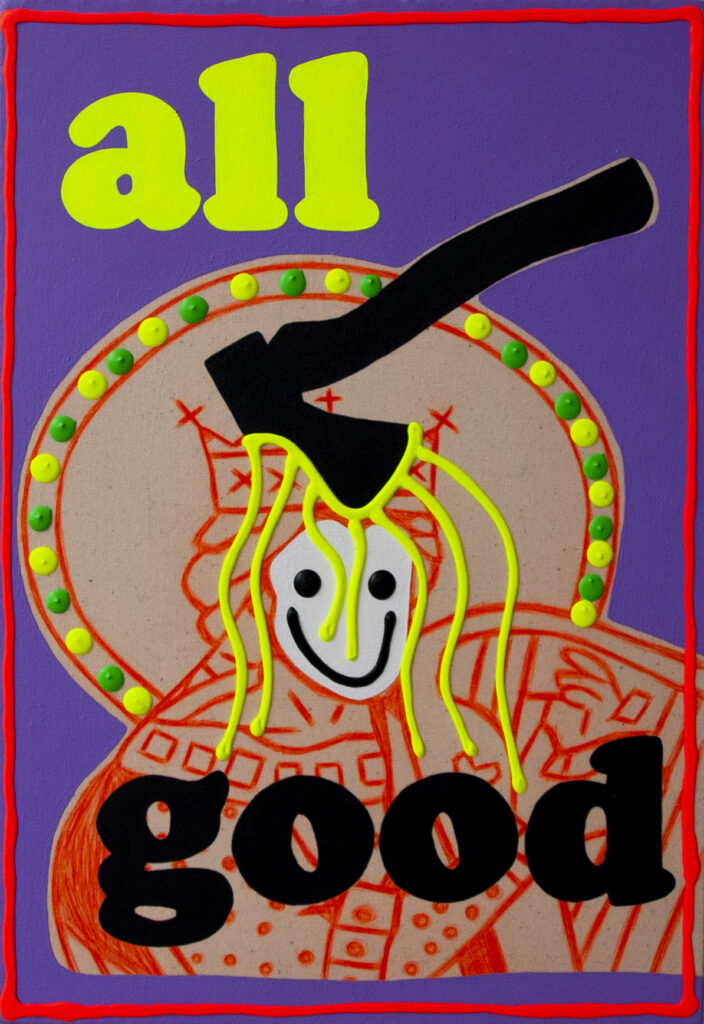

Kennet Lekko – Estonian artist, living and creating in Berlin

War is something that makes a person radically rethink everything. The question of the usefulness of my chosen profession has been haunting me lately. Watching men my age – from cooks to IT specialists – pick up weapons and defend their country is a powerful image. And here I am, in my studio in Berlin, 29 years old and healthy, making pictures for a living. Thinking about composition and colour schemes.

A cook can be useful in war, but can a painter? As a rebellious teenager who harboured a problem with authority of any kind, I refused to go to the army and found my way around it. Some years later I changed my mind on the topic, but by then I had moved on and I was already building my life in another country. I have never held a weapon; I don’t think I have even been in a fistfight that could’ve led to any serious bodily harm. But now I wish I had. Just to be ready. Because conflict tends to happen, whether you are prepared for it or not.

Some might see culture as an accessory to life, something to be enjoyed when our basic needs are met. Others might argue that culture gives meaning to life, both in good times and bad. A poem or a song or a painting can make suffering tolerable.

Art has also been used as propaganda for both positive and negative causes. But I don’t think art should tell people what to think. It should give the audience a direction, pose questions and provoke thought. Of course, there are artists and artworks that tackle issues directly, but this has never been my approach and I think it’s best left to those who do it better than I ever could.

I like to think that my work can have multiple readings, and going through some older pieces in today’s context gives me an uneasy feeling at times. Suffering, doubt and looking into the darker spheres of existence seem to run through most of it. But more on a personal and slightly metaphorical level. But there is little that is metaphorical about an airstrike. What is an artist to do in such times?

On a practical note, it is great to see people from all walks of life come together during tough times and do what they can to help. It has been heart-warming to see solidarity gatherings, charity concerts, art auctions and more spring up over the past few weeks, and I am looking for ways to help such initiatives raise funds myself.

Most of all, I think it is important to stand united and not let this situation dissolve into the background, becoming something that we tolerate over time. I would like to think that art in any form can offer solace, inspire, provoke thought and perhaps comfort to people in times of war and peace alike.

I hope that artists will not become lazy or give up. That they keep their integrity and don’t let the lines between culture and propaganda blur. And that the existence of art – good or bad, uplifting or pessimistic – reminds people that freedom of thought and expression is not a given and are worth fighting for. If a pen is mightier than a sword, then I hope a brush or a guitar has the chance to stand against a tank. If not immediately, then in the grand scheme of things.

Art reflects life and artists find ways to reflect on difficult topics, while also inspiring in difficult times as well. I am young enough to be idealistic, but not young enough to be so naïve that I am blind to the possibility of darker scenarios.

I will keep working on compositions and colour schemes and ideas as long as it is possible. And if, God forbid, it is not anymore, I, along with countless other artists, cooks, IT specialists and people from all walks of life will have to figure out how to make a peaceful world possible again. Of course, I hope I will never have to hold a weapon.

Ellen Meriny – French abstract artist, living and creating in Tallinn

First of all, works of art are an effective means of denouncing war and violence. Indeed, art allows us to reach a wider public because it has the possibility of being presented in multiple forms and in multiple places.

Some of these art forms have a universal and international language, understandable whatever the age and the language of the viewer. Artists can convey important messages about war. They can reveal to everyone a fact, an event that will provoke strong emotions and awareness. Art can denounce, but it can also bring people together. Artistic events, like solidarity concerts, are an essential opportunity to come together and share emotions of fear and sadness triggered by war, while also conjuring hope for a better future, one in which peace takes over.

Finally, art has therapeutic powers. War and suffering are traumatic events that have a terrible impact on our mental state. Anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress are the direct consequences of these traumas. Art and creativity can help us mitigate the devastating effects of these consequences. Art as therapy uncovers buried emotions associated with traumas in ways that differ from traditional communication. Moreover, creativity promotes resilience because it unlocks inner resources for dealing with stress, solving problems and enjoying life.

I have chosen to share with you “Flower power”, as a symbol of non-violence and hope. “Flower power” was created in Tallinn.

Jana Soans/VJ Solaris – Estonian projection artist

Art helps you resist and offers hope.

Abraham Kenny – Australian musician and songwriter, living and creating in Tallinn

Every second day I play at Balti Station tunnel in Tallinn, I get a sense of the mood on the street – people have been very generous and kind, but, since the war in Ukraine began, I have felt my voice and demeanour diminish.

That was until one Estonian painter stopped me and said, “Sing me a song’”. So I did and he said, “You are not singing”. And so I told him why – that I had lost my voice. He told me that as an artist (and as the dregs of society that we are), it is important to always do what you do with strength – especially now. So I performed another song for him – this time it was better, and he bought two of my CDs. This guy helped reaffirm my belief in art and music, as I really don’t know what else to do right now.

I wrote a song in 2020 about war and recently posted it online with a video.

While I was in Ukraine in 2018, I saw the effects of war though on a relatively subtle level. A mother attending her young son’s grave in a cemetery, a soldier at the train station with the same look I had seen in a relative who also served in a war.

Then I also spent quite a bit of time in Kemeri, Latvia, where a lot of Soviet veterans of the Afghan War live – in wheelchairs, as alcoholics. I played a concert there and a Latvian soldier who had recently served in Afghanistan as part of the NATO mission was in the audience. He was very moved by the concert and suggested that I play for the soldiers, as they would understand my music – people who have seen the other side. This was the greatest compliment my music had received.

I wrote this song around the time that atrocities – namely, the use of chemical weapons – were being committed against Syrian civilians. I also had in mind the story of a friend’s best friend who suffered from depression and who had moved to Australia from Poland, only to take her life there. In this last case, I could relate to the sense of profound alienation. I was not necessarily writing about these things directly, but often when we create, we don’t know exactly what we are writing about.

A song may seemingly be about heartache, but heartache can open us to a broader, more worldly suffering. I chose to live in Eastern Europe because the emotional environment here is similar to my own. Negativity – suffering, trauma, etc. – is part of the culture and people need collective ways of expressing grief. Younger countries, such as Australia where I am from, lack this viewpoint.

The ability to create from negative states is, to me, the very essence of culture. I do not celebrate suffering, nor do I want it, but I hope that my music can help people as I suffer for it for some reason, and it helps me deal with these heavy feelings.

In saying all that, making music and art right now can feel all but futile, like the only language the world understands is violence and coercion. It’s not as if anything I or anyone else makes is going to bring back the dead, so I am not kidding myself with a false sense of importance. I’m simply continuing to do what I have always done, and perhaps it will be of use to someone at some point.